Science Internship Program: Virtual Reality / Physical Escape Room

Researching how to create different collaborative dynamics in escape rooms through designing a combined physical and virtual escape room.

I co-mentored a summer-long research project as part of the UCSC Science Internship Program. I, a fellow graduate student mentor, and a team of four high school students worked together on creating an escape room that mixed virtual reality (VR) and physical space. In this escape room, two participants are placed in the same room but one participant wears a VR head-mounted display (HMD) and thus can only see and interact with objects in the virtual space. The other participant can only see and interact with objects in the physical space. The players must work together with asymmetric information to solve puzzles and escape the room as a team.

Background

We began this project by looking at existing literature on escape rooms and cooperative play. We were particularly interested in the affordances of escape rooms and design in this space, as well as the overlap between physical and digital spaces in games. Part of the reason we settled on creating an escape room that mixed physical and virtual reality was a practical one--our high school students were interested in learning aspects of game development, and we had experience with VR development. But part of the reason was also because we found this space to be under-explored in the design of escape rooms, and wanted to see how we could examine this space by designing our own escape room to look at the affordances of the mixed spaces as well as communication and cooperation between the two asymmetric roles through design.

Existing literature for escape rooms was rather limited. We looked and drew from the work of Scott Nicholson, who has written several papers on escape rooms as well as a survey on existing escape rooms in order to better understand and categorize the techniques they use (2016a) (2016b). We also found several readings analyzing escape room play, including Pan et al. (2017) looking at how people work together and communicate to solve escape rooms, and Zhang et al. (2018) on how gamification and escape room solving builds teamwork. There are also escape room papers in which researchers build and evaluate escape rooms with the use of non-conventional technology in the escape room design space, such as Warmelink et al. (2017) which looks at the use of mixed-reality in escape rooms and its effects on teambuilding, and Shakeri et al. (2017) which looks at player collaboration for distributed escape rooms (where players are in different spaces). While there are entirely physical and entirely VR-based escape rooms (Stolee 2021), we were interested in combining these two mediums. From what we could find, there hadn’t been any work done on creating an escape room that mixed players in physical and VR spaces.

The design of the escape room

The escape room was designed and assembled in UCSC’s user testing lab using Unity for development, an HTC Vive for development and testing, and a BreakoutEDU kit that provides various adjustable locks and boxes. We began creating the VR portion of the escape room in Unity by measuring out the size of the user testing lab and the large furniture in that space that we would be using for the escape room (table, chair, TV), creating 3D assets that matched the physical room and making sure that the VR space and the objects within it were roughly the same size as in the physical space so that the VR participant would not accidentally walk into the furniture or walls. The physical room and virtual room were also oriented in the same way such that a player standing on one side of the physical room (ex. the right side of the room) and a player standing on the right side of the virtual room would be physically next to each other.

The puzzles

We created a series of puzzles that would give different control to the two different players by requiring different tasks such as information retrieval and puzzle-solving by different players at different times. The escape room consisted of the following sequence of puzzles (photos below the puzzle descriptions):

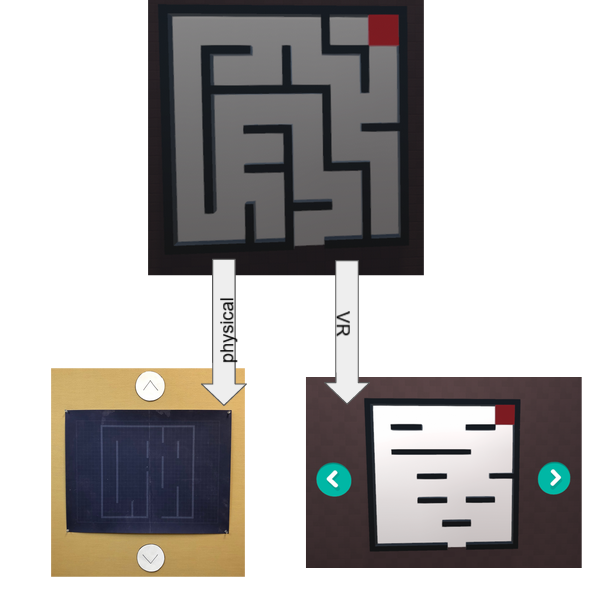

- Maze puzzle -- the players must work together to solve a maze, guiding a cube in the virtual environment through a maze on the wall. The player in VR can only see the maze’s horizontal walls. The player in the physical space can see a poster of the same maze, but can only see the vertical walls of the maze. The player in the physical space can move the cube through the maze using a keyboard, but can only move the cube up and down. The player in VR can move the cube using buttons in VR, but can only move the cube left and right.

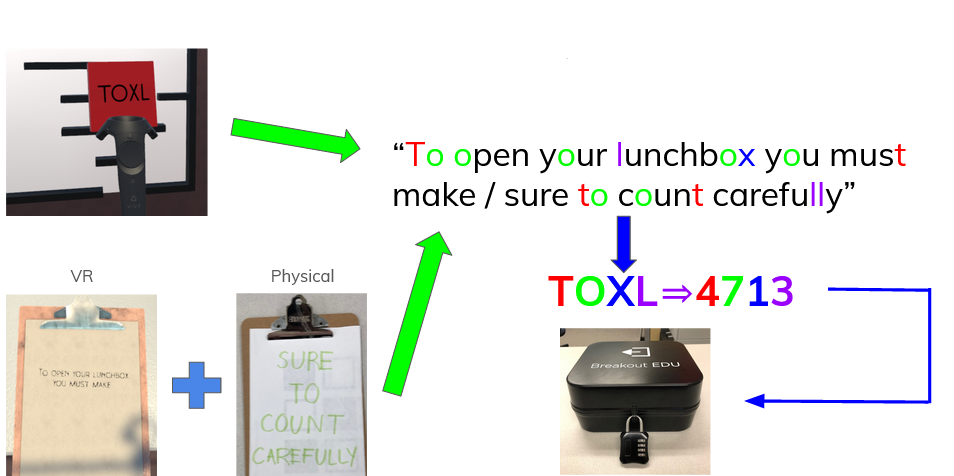

- Text puzzle -- After solving the maze, the VR participant can now see the back of the red cube that was trapped in the maze, which has the code TOXL. Both the physical and virtual environments have clipboards in them, which each contain half of a sentence. The VR player’s sentence says “To open your lunchbox you must make” and the physical player’s sentence says “sure to count carefully.” The players must combine the sentences together and count up the number of times the letters T, O, X, and L occur in the sentence. This is the code to open a locked box (the player’s “lunchbox”) in the physical room.

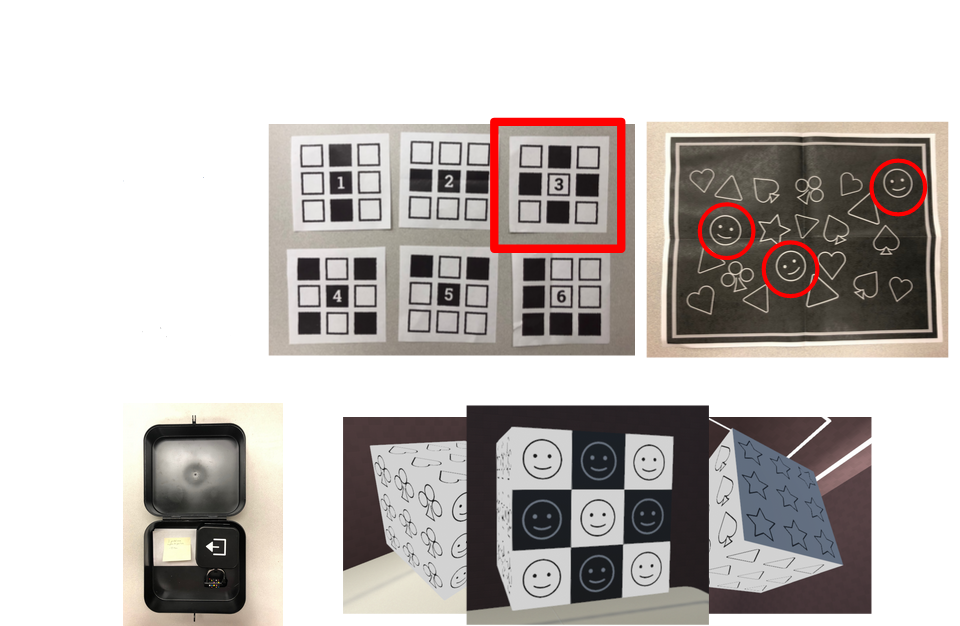

- Cube puzzle -- The player in the physical space can find around the room various notes with 3x3 grids of black and white squares. After opening the box from the previous puzzle, that player also finds a reference poster with various symbols on it. The symbols and the grids correspond to the symbols seen on a 3x3x3 floating cube in the middle of the VR room. The player in the virtual space must interact with the faces of the floating cube, turning them black or white, according to the patterns on the physical player’s notes. The cube face that corresponds to each symbol is depicted by the number of times that symbol appears on the reference poster. For instance, if the smiley-face symbol appears three times on the reference poster, the player in VR must use the pattern with the number 3 in the center, coloring black the faces in a cross pattern (not including the center). This will make the cube disappear.

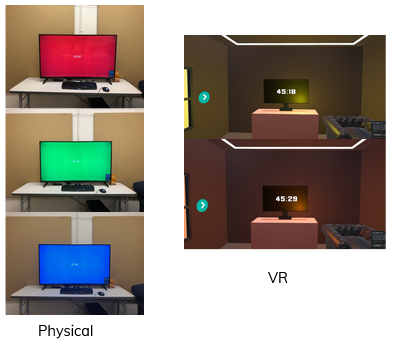

- Light puzzle -- After solving the cube puzzle, the area around the TV in virtual space and the computer monitor in the physical space will begin flashing various colors and playing various alarm sounds, which will sound like a certain number of beeps. The player in physical space will see the monitor flash red, blue, and green, while the player in virtual space will see alarm lights as yellow and orange, with a different number of beeps for each color. The number of beeps for each color corresponds to the order of colors needed to open a color-coded lock on the box found after solving the text puzzle. Opening the last box provides the players with the key that they need to escape the room.

Other design considerations

In thinking through the design of the escape room, there were a few other design considerations that we thought would influence the game, but only made it into the finished game to a smaller degree.

- Theme -- In thinking up possible themes for the game, we played around with the idea of making the players conspirators working on a heist together. The flashing lights and sounds puzzle (the last puzzle of the room) would resemble alarms going off once the player has succeeded in their task, and imply a sense of urgency. This is also why some of the clue parts are hidden in an innocuous “lunchbox,” a disguise that the players presumably used to get tools for the heist into the room without being seen. Although the theme didn’t make it strongly into the final game, it did influence some of the puzzle development. We also theorized that the player in VR might thematically be seeing the room in some augmented way, for instance as one might see the room with AR augmentation. This provides the benefits of AR without letting the second player see or interact with the physical room components, preserving the asymmetric roles and information. Still, a future improvement to the theming of the room could explain why the player in VR can only see some elements of the physical room and not others (while someone in AR should be able to see both the physical and augmented spaces).

- Rewards -- One area that we were interested in exploring is having a reward system besides just the standard time to completion common to most escape rooms. We created a variant that introduced a secondary resource that the players could gather--following the heist theme, this was represented as money--which was earned by the players for solving puzzles. Money can be spent by players to get hints throughout the game, which would reduce the player’s overall earned score but allow the players to escape.

- Penalties -- We were also interested in how a penalty system might affect play. We created a variant that penalized players for inputting incorrect solutions to puzzles--for instance, moving the block into the wall of a maze in the maze puzzle. This would subtract time from the total time that the players have left to solve the puzzle. We believe that this would help to prevent players from brute-forcing puzzles. This could also be frustrating to players, however, discouraging exploration and interaction with the play space.

Reflection

The main goal of this project was to explore the design of a co-located escape room that mixed virtual reality and physical space. One of the issues with existing escape rooms that we wanted to help address was the problem of quarterbacking, where one player might try to rush ahead and solve all of the problems. We were interested in how using the two different spaces for different players might help to mitigate this problem, because the players can only see and solve problems in their own domain. They can still get assistance from their partner by verbally describing what they see, but solving the puzzles (including both reasoning about what to do and the physical enactment of solving the puzzle) would be left to each individual player.

We also wanted to explore the interaction between players in the physical and virtual spaces, fostering cooperation between them through asymmetric information-sharing. Escape rooms have multiple kinds of challenges for players, including “searching” challenges where players look for items physically hidden in the space, “puzzles” where players must discover an answer (such as the code to a padlock) based on clues, and “tasks” that players must perform such as solving a maze (Nicholson 2016b). A single challenge might string together searching, puzzles, and tasks, requiring players to use a combination of these methods to progress. Because of the asymmetric information and spaces created by overlapping the physical and virtual escape rooms, we could divide these steps of the puzzles between both spaces, ex. Player A finds information and shares it with Player B, which Player B can then use as part of executing a puzzle’s solution. We wanted to split up the various parts of each challenge as much as possible to encourage collaboration between players. In some cases, this was structured in such a way that one person has information and the other person executes a puzzle (such as the cube puzzle). In other cases, both players have partial information and control (such as the maze puzzle). This also meant making the links between the physical environment and the virtual environment clear--that is, players should know when an item in the virtual room and the physical room were meant to be part of the same puzzle.

Overall, I think that this escape room is an interesting start to looking at how to design a physical / virtual co-located escape room. All of these puzzles were designed such that neither player could solve the entirety of the puzzle on their own. Instead, players must communicate and cooperate to solve puzzles together. There are certainly ways that the design of the escape room could be improved upon, particularly in regards to theme--a stronger theme would give players more context and help to ground puzzles more, as well as give players a stronger motivation to complete the room rather than just solving puzzles for their own sake. We are also interested in further exploring how variants to the game, such as the money and penalties--might affect play. There are also other ways of creating collaborative puzzles in the co-located space that we did not explore, such as greater use of sensory puzzles (such as auditory puzzles) and greater use of enactment, such as having one player have to physically guide the other player through the space. I hope to further explore these aspects of escape rooms in future work.

Works Cited

Nicholson, S. (2016a). Ask why: Creating a better player experience through environmental storytelling and consistency in escape room design. Meaningful Play. Retrieved from http://scottnicholson.com/pubs/askwhy

Nicholson, S. (2016b). The state of escape: Escape room design and facilities. Meaningful Play. Retrieved from http://scottnicholson.com/pubs/stateofescape.pdf

Pan, R., Lo, H., & Neustaedter, C. (2017, June). Collaboration, awareness, and communication in real-life escape rooms. In Proceedings of the 2017 conference on designing interactive systems (pp. 1353-1364).

Shakeri, H., Singhal, S., Pan, R., Neustaedter, C., & Tang, A. (2017, October). Escaping together: the design and evaluation of a distributed real-life escape room. In Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play (pp. 115-128).

Stolee, M. (2021). A descriptive schema for escape games. Well Played, 5.

Warmelink, H., Mayer, I., Weber, J., Heijligers, B., Haggis, M., Peters, E., & Louwerse, M. (2017, October). AMELIO: Evaluating the team-building potential of a mixed reality escape room game. In Extended abstracts publication of the annual symposium on computer-human interaction in play (pp. 111-123).

Zhang, X. C., Lee, H., Rodriguez, C., Rudner, J., Chan, T. M., & Papanagnou, D. (2018). Trapped as a group, escape as a team: applying gamification to incorporate team-building skills through an ‘escape room’ experience. Cureus, 10(3).